Chapter 1: The Long Game

The best way to have a better (healthier) future is to start planning for it now. Focus not on preventative medicine, but on proactive medicine.

Longevity: Lifespan and Healthspan

Longevity has two components: how long you live (lifespan) and how well you live (healthspan). It is deeply rooted in science, but it is also an art that needs to be sculpted to each individual. It is more malleable than you think. Ultimately, it demands we prevent chronic conditions.

Healthspan is not just about being disease and disability free. It’s also about the quality of that life. Its deterioration happens with:

- Cognitive decline

- Loss of function of physical body (muscle mass, strength, stamina, stability)

- Degeneration of emotional health

With enough time and effort you can potentially extend your lifespan by a decade, and your healthspan by two, meaning you can function like someone 20 years younger than you. This book shows you how.

Modern Medicine

Death comes fast (accidents) or slow (disease).

Skills acquired in medical schools are far better at preventing quick death than slow death. Doctors can relieve symptoms of chronic disease, and delay end slightly, but cannot reset the clock like they can with acute problems. Modern medicine has thrown a lot at chronic illness, but hasn’t moved needle far. (Except for heart issues, which has decreased by 2/3 in last 60 years.) Cancer deaths have hardly budged in last 50 years. Diabetes is a crisis, and there is no treatment for Alzheimers.

Modern medicine approaches trauma and chronic patients with the same basic script: stop the patient from dying. With chronic patients, we are intervening at the wrong point in time. Even when someone dies “suddenly” of a heart attack, the disease had likely been progressing in their coronary arteries for two decades. Slow death moves even more slowly than we realize.

The Four Horsemen

These are: heart disease, cancer, neurodegenerative disease (eg alzheimer’s) and type 2 diabetes. They cause slow death. The prevalence of each Horsemen increases sharply with age – they begin much earlier and take a long time to kill you.

Each of the Horsemen is intricately complex, more of a disease process than an acute illness like a common cold. They are cumulative, the product of multiple risk factors adding up and compounding over time. The good news? Many of these individual risks are relatively easy to reduce or eliminate. We need to step in sooner than we are to stop the Horsemen in their tracks, or better yet prevent them all together.

Chapter 2: Medicine 3.0

“The time to repair the roof is when the sun is shining” – John F. Kennedy

Medicine 1.0 was exemplified by Hippocrates who determined that diseases are caused by nature and not by the actions of the gods. Conclusions were based on observation and guesswork.

Medicine 2.0 arrived mid-nineteenth century, with germ theory. Discovery of penicillin was the real game changer. The shift from Medicine 1.0 to 2.0 took centuries, and met with much resistance along the way. Medicine 2.0 has eradicated deadly diseases (smallpox) but it has been less successful against long-term diseases like cancer.

Medicine 3.0 pays far more attention to maintaining healthspan (the quality of life). The goal is to prevent the Four Horsemen (heart disease, cancer, neurodegenerative disease, type 2 diabetes). Our treatments and prevention/detection strategies need to change to fit the nature of these diseases. Medicine 3.0 requires patients to be involved, medically literate, clear-eyed about goals, and cognizant of the true nature of risk.

In Medicine 3.0, you are the captain of your own ship.

(We have the promise of more data on patients, artificial intelligence and machine learning, and nanotechnology. But our idea of personalized medicine remains some distance ahead of the technology necessary to realize its full promise. )

Chapter 3: The Strategy

Our objective is to delay death, and to get the most out of our extra years. The rest of our life needs to be relished, not dreaded.

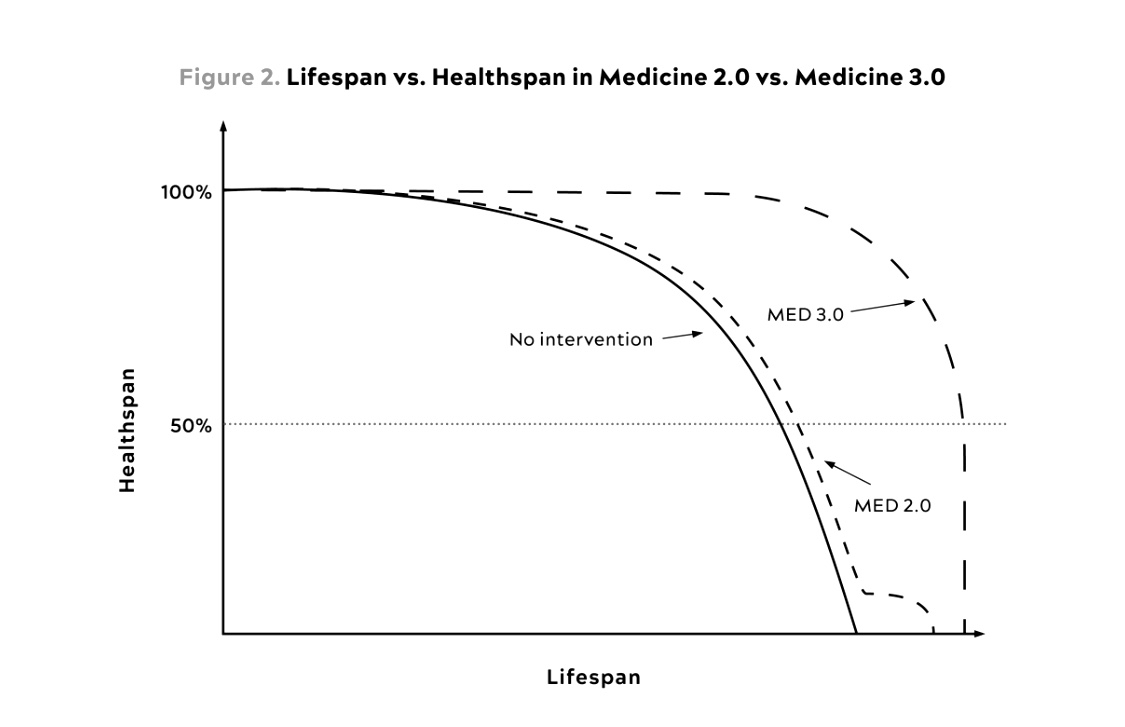

The graph

The solid line is the medicine 1.0 type of life….your healthspan declines in old age rapidly, and then you die.

The Med 2.0 line shows a similar decline of your healthspan, except that now the medical intervention in the last stages of your life (the horizontal kink) extends your life by 10 years or so. Unfortunately, those 10 years are spent when your healthspan is at its lowest. The medical intervention extends our lifespan, but not our rapidly declined healthspan.

The Med 3.0 line shows proactive intervention, way before any problems are known. By taking certain measures, you might actually increase your healthspan (feel better than you ever would have), and will enjoy your last decades with a healthy healthspan.

The Strategy

The strategy to longevity is to delay all Four Horsemen (heart disease, cancer, neurodegenerative disease and type 2 diabetes). Since the Horsemen have one common risk factor – age – the strategy must account for effects of aging ie cognition and physical ability. Emotional health is the third equally important component to longevity.

To understand the importance of cognition, physical ability and emotional health, think of your list of “daily living activities” ie the things you want to be doing in your old age. Examples: prepare a meal for yourself, bath, groom, use phone, grocery shopping, carrying groceries into the kitchen, maintaining your finances etc. These abilities go away slowly if we don’t take action.

If we want sufficient levels of cognition, physical ability and emotional health, we need to improve them and/or slow their degeneration. We can do that with proper tactics. The tactics fall into 5 domains:

- Exercise (increasing strength, stability, aerobic efficiency, peak aerobic capacity)

- Nutrition (how much you eat)

- Sleep

- Emotional health

- Medicine, supplements, hormones

In the next chapters, we will learn how to use each of these tactics to increase our healthspan.

Chapter 4: Centenarians

Centenarians – those who live past the age of 100 – tend to have been biologically younger than their peers their entire lives. They are often healthier at 90 than the average person is at 60. If they succumb to the Four Horsemen, it’s usually decades later than the average person. Not only do centenarians enjoy two or three bonus decades, when they die, they have been sick for a much shorter period of time than the rest of us. This is the effect we are trying to mimic.

How do centenarians delay or avoid chronic disease? The short answer is that we don’t know. It could be luck and resilience. They are certainly no more health-conscious than the rest of us.

Could it be genes? There is no such thing as a “perfect” centenarian genome: they have very little in common with each other genetically, although there are a handful of genes that might be relevant to our search for longevity. As we will see in next chapters, even if we don’t have those specific genes, we can mimic their function through gene expression (switching on and off of other genes) which we control with our behavior (example: restricting our calorie intake).

The fact that there is no “perfect” longevity gene is good news for the rest of us. It means that the longevity game is a game of inches where relatively small interventions, with cumulative effect, can help us replicate the centenarians’ longer lifespan and healthspan.

Chapter 5: Eat less, live longer?

Note from Eve: This is a “science-intense” chapter. You can read the science, but you don’t have to. The conclusions stand either way, of course. I follow my late dad’s advice here. When he feared I was about to enter into a long winded story, he told me to “start at the end, please”. For more details, see the book 🙂

Autophagy

Autophagy is a form of recycling junk out of cells. It’s essential to life. Cells then run more efficiently, and are more resistant to stress. It also removes clumps of damaged proteins, which have been implicated in Alzheimers and Parkinsons.

Autophagy declines as we get older, and impaired autophagy is thought to be an important driver of numerous aging related phenotypes and ailments, such as neurodegeneration and osteoarthritis, which is exactly what we want to avoid in our pursuit of longevity. So it is significant that it can be triggered by certain kinds of interventions, such as temporary calorie restriction (when exercising or fasting) and the drug Rapamycin.

Caloric Restriction

Caloric restriction without malnutrition (CR) is an experimental method where one group of animals eats as much as they want, and another group is given all the essential nutrients but 25% less calories. The results are remarkably consistent: CR improves lifespan and healthspan and seems to cause cells to go into a mode activating autophagy.

Nevertheless, the author does not advocate calorie restriction as a means to promote longevity, because its effects remain doubtful outside the lab, there is no evidence that it extends longevity in humans (who live in more variable environments) and because its benefits might be offset by infections, trauma and frailty (due to less nutrition). Also, long term calorie restriction is difficult to sustain for most people and thus not a realistic path to longevity.

Rapamycin

The drug offers more hope. It significantly promotes the lives of mice, and has a strong potential as a longevity drug.

Unfortunately, it also has serious negative side effects. Rapamycin is currently prescribed for organ transplant patients for whom it suppresses immunity, thus reducing the risk of organ rejection. Understandably, it is not wise to take a drug that severely compromises immunity in healthy people. But, in a very encouraging development, it has recently been shown that rapamycin can also act as an immunity enhancer under different, and specific dosages. It is not realistic or responsible to test the drug on healthy patients, so it is being tested on 600 pet dogs. So far, results strongly suggest that it might improve cardiac health, minimise inflammation and even aid in cancer detection. Results are expected in 2026.

Positive study results might eventually lead to more use of the drug for longecity purposes in humans. The author already uses the drug off label for this purpose, for himself and his patients, and believes that taking it cyclically does reduce negative side effects.

If the drug was used in healthy humans to promote longevity, this would be a move towards Medicine 3.0: given to seemingly healthy people to prevent future disease, or slow down aging. It wouldn’t pass under Medicine 2.0 mantra, where a patient would have to already be visibly sick to receive the drug.

Metformin

This is another drug that might be used for longevity. It is currently used by diabetics, and is shown to incidentally reduce cancer risk. The FDA has given greenlight for a trial which is testing whether giving metformin to healthy subjects delays the onset of aging related diseases, as a proxy for its effect on aging.

Chapter 6: The crisis of abundance

To promote longevity and healthspan, we need to get our metabolic house in order. To do that, we need to understand it.

Metabolism

Metabolism is the process of taking in nutrients, and breaking them down. For use in the body. If we are metabolically unhealthy, many of the calories consumed end up where they are not needed, or where they are actually harmful.

How metabolism works

When we eat a doughnut, the body decides what to do with the calories in that doughnut. First, it can be converted into glycogen, which is suitable for use in the short term. The liver converts this glycogen to glucose. We usually have enough for about 2 hours of vigirous exercise. Second, the calories can be stored as fat. The decision of which of the two places to store the fat is made by hormones, chief of them insulin which is secreted by the pancreas. Insulin helps shuttle the glucose (the final breakdown of most carbohydrates) to where it is needed in the body. You will either consume it immediately, or it will be stored as fat. Storing it as subcutaneous fat is actually a very safe and good place to store it. When we need more energy, some of that fat is released for use by our muscles. As long as we don’t exceed our fat storage capacity, things are fine.

But if we continue to consume calories, and fill up all our fat storage, our body has to find a new place to store the fat: in our blood (excess triglycerides), our liver, muscle tissue, and even around our heart and pancreas, our abdomen in between the organs. This “visceral fat” is dangerous, and drives up inflammation. You are at risk of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

Metabolic Syndrome (MetSyn)

Marked by:

- High blood pressure (>130/85)

- High triglycerides (>150mg/dL)

- Low HDL cholesterol (< 40 mg/dL men, <50 mg/dL/women)

- Central adiposity (waist circumference >40 inches in men or >35 in women) (obesity)

- Elevated fasting glucose (>110 mg/dL)

By Medicine 2.0 standards, metabolic syndrome is diagnosed if three or more of these are present (which is true for 120 million Americans!). By Medicine 3.0 standards, even if we only have one of these, it’s already bad news and action needs to be taken. (This is true for 90% of US adult population.) We need to intervene before patient develops metabolic syndrome.

Note that obesity (BMI>30) is only one of the symptoms of metabolic syndrome. Not everyone obese is metabolically unhealthy, and not everyone metabolically unhealthy is obese. You can be thin and not overweight and still be metabolically unhealthy. It’s not about how much you weigh.

Metabolic syndrome decreases longevity and healthspan by increasing chance of cancer, heart disease, alzheimer’s etc.

Insulin Resistance

Occurs when cells stop listening to insulin signals. As we’ve seen, when cells are full of glucose, the glucose enters the bloodstream. Sensing this, the pancreas secretes more insulin to try and remove the excess glucose from the blood, and cram it into the cells. This works for a while, until there really is no more space in the cells. That’s when we see elevated fasting blood glucose levels. This means we have high insulin levels and high blood glucose levels, and cells are shutting the gates to more glucose. As things get worse, the pancreas becomes fatigued, fat (glucose) gets stored between the organs (including the pancreas) and this creates a vicious cycle of more fat, more overworked pancreas, and more problems. Visceral fat in muscles leads to insulin resistance, especially if there is a lack of exercise.

Insulin resistance increases the odds of cancer (by up to 12x), alzheimers (by up to 5x), death due to cardiovascular disease (by up to 6x).

Insulin resistance on its own should be treated as a disorder (but isn’t).

Why is this happening now?

Our diet. We eat too much, and we eat more of the wrong things.

Fructose is a big problem, because it causes a build up of uric acid, which in turn leads to high blood pressure and fat gain. Too much fructose overwhelms our gut, and goes to the liver where it is deposited as fat.

To promote longevity and healthspan, we need to get our metabolic house in order. We do this through exercise, nutrition and sleep (see next chapters).

Chapter 7: The Ticker

Heart Disease is more easily prevented than cancer or Alzheimer’s. It’s easy to delay and we already have the necessary scans and medicine to help with diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Although it is still our main killer, with a correctly timed strategy death from heart disease could be prevented all together. Half of all cardiovascular events occur before the age of 65yrs – we need to start preventing and treating heart disease much earlier than we do – as early as our 30s and 40s.

Cholesterol and apoB

Heart disease is not caused by the cholesterol we eat: most of that is excreted. There is no connection between food we eat and cholesterol in our blood. The vast majority of our cholesterol is produced by our own cells. We should lose the concept of “good” vs “bad” cholesterol because that is not what is causing cardiovascular events.

Our blood transports oxygen and nutrients, as well as cholesterol. Because cholesterol belongs to fat family, it is not soluble in the plasma, and needs to be transported in little “cargo submarines” called lipoproteins. The lipoproteins are wrapped in large molecules, and one of these molecules – the apoB – is present in every lipoprotein that causes cardiovascular problems. The lipoproteins with apoB proteins tend to get stuck in the arterial walls, get oxidised and build up to cause serious further problems – that take a very long time to show up on scans and tests. The more apoB there is in the bloodstream, the higher chances they get “stuck”. Hence, reducing the levels of apoB is essential to reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease, even if we do not see anyother “evidence” of heart disease.

Lp(a)

Lp(a) is a specific type of apoB, and is particularly destructive to arteries and the aortic valve. Most people have a small concentration of this particle, but some people have 100 times what “regular” people have. This applies to about 20-30% of the population, and it is genetic. It is also the most prevalant hereditary risk factor for heart disease. Test your levels of Lp(a) so you know where your risk lies (you only need to test once).

Unfortunatelly, there is no quick fix for high levels of Lp(a). It doesn’t respond to interventions like diet or exercise. A drug class known as PCSK9 can lower the prevalence by 20-30%, but does not lower the frequency of adverse events associated with high Lp(a) levels. The only real treatment is aggressive lowering of apoB overall. Lower that, and you lower your overall risk.

Lowering apoB

apoBs are causally linked to heart disease and stroke. Remove the cause, and you remove the disease.

The apoB level can easily be measured with an affordable test, and you should have yourself tested regularly. Then, get it as low as possible, as early as possible. How low? The author advocates a LDL-C target of 10-20 mg/dL, which is considerably lower than the 70mg/dL target sugggested by Medicine 2.0 doctors.

You can lower apoB by getting your metabolic house in order (see Chapter 6). Diet can help lower your triglycerides and manage insulin. (see next chapters).

But drugs need to be used in tandem with nutrition. Statins are a class of drugs that take LDLs out of circulation, thus lowering apoBs. You should use them.

Lastly, remember that heart disease unfolds over decades, not years. Nearly all adults are coping with some sort of vascular damage already, no matter how young they seem or how pristine their arteries look on scans. We need to think about prevention starting now.

Your strategy to reduce heart disease should include:

- Reduce apoB as much as possible, as soon as possible

- No smoking

- Control blood pressure

- Intervene much sooner

Chapter 8:

Today, cancer kills Americans at almost exactly the same rate as it did fifty years ago. Of all the Horsemen, it is the hardest to prevent and early detection is our strongest arsenal. Once cancer is established, we lack highly effective treatments for it. Tumors can be removed surgically, but that is of little value if cancer has metastesized (spread): metastatic cancers can be slowed with chemotherapy, but they virtually always come back, often more restitant to treatment than before.

The Strategy

In Medicine 3.0, we have a three prong strategy for dealing with cancer:

First is to prevent getting it alltogether. Cancer prevention is tricky because we do not yet understand what drives the initiation and progression of the disease with the same resolution as we understand heartdisease.

Second, we can rely on newer and smarter treatments targetting cancers’s weaknesses, especially immunotherapy.

Third – and best – we need to try and detect cancer as early as possible so that our treatments can be deployed more effectively. This requires early, aggressive and broad screening. With a few exceptions (brain, lung and liver cancers) solid organ tumors typically kill you only when they spread to other organs.

Metabolic dysfunction

It is hard to ignore the link between cancer and metabolic dysfunction. Excess weight is a leading risk factor for cancer cases and deaths, second only to smoking.

Obesity is strongly associated with thirteen different types of cancers and when accompanied by accumulation of visceral fat, it also promotes inflammation. This could create a cancer-friendly environment. Obesity also contributes to insulin resistance, itself a bad actor in cancer metabolism.

Therefore metabolic therapies, including dietary manipulations that lower insulin levels, could reduce cancer risk and slow down growth of some cancers. Fasting, or a fasting-like diet, increases the ability of normal cells to resist chemotherapy, while rendering cancer cells more vulnerable to the treatment.

Immunotherapy

An immunotherapy is any therapy that tries to boost or harness the patient’s immune system to fight an infection or other condition (example: vaccines). So for a cancer immunotherapy to succeed, we essentially need to teach the immune system to recognize and kill our own cells that have turned cancerous. It needs to distinguish “bad self” from “good self”. Great strides are being made in this regard, but we are unlikely to get a blanket “cure” for cancer any time soon.

Early detection

When cancers are detected early, in stage I, survival rates skyrocket. At that point, there are fewer total cancerous cells, with fewer mutations, and they are thus more vulnerable to treatment with drugs that we do have. The lower the patient’s overall tumor burden, the more effective the drugs tend to be.

Unfortunately, our ability to detect cancer at an early stage remains very weak. We most often discover tumors when they cause other symptoms, by which point they are advanced or metastasized. Out of dozens of different types of cancer, we have reliable screening methods for only five (lung, breast, prostate, colectoral and cervical) and visual examination for skin cancer and melanomas.

(The author advocates a colonoscopy by age forty, and sooner if anything in patient’s history suggests they may at higher risk. It should be redone every 2-3 years).

If possible, you can opt for “private” screenings and tests but be aware that aside from the obvious financial cost, there is also an emotional one. If you’re going to have a whole-body screening MRI, there is a good chance your medical team will be chasing down an insignificant nodule in exchange for getting a good look at your other organs. This can be stressful, but it is better than the risk of doing nothing.

There is also a growing technology of “Liquid biopsies” or blood tests that are being used to test for cancer recurrence, tumor biology as well as for new cancers. This is a developing field.

In any case, no single diagnostic test for anything is 100% accurate, and so it is best to stack test modalities – example incorporating ultrasound and MRI for breast cancer.

There is rarely only one way to treat cancer successfully. The best strategy to target cancer is to likely by targeting multiple vulnerabilities of the disease at one time, or in sequence example, drugs and nutrition.

Chapter 9:

Alzheimer’s is the most intractable of the Horsemen diseases. We have no way to treat it once it begins, and it is likely not readily reversible. Medicine 2.0 cannot help us: Once it is diagnosed, little can be done. We must rely on Medicine 3.0 concepts of prevention and reduction.

Dementia can progress unnoticed for years before any symptoms appear. (Loss of sense of smell is one early sign). People with a history of cardiovascular disease or metabolic dysfunction are at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Having type 2 diabetes doubles or triples your risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Insulin seems to play a key role in memory function.

APOE is the gene related to Alzheimer’s disease risk. The e4 allele, specifically, is what increases the risk, possibly because it also plays a role in inflammation.

What helps prevent dementia?

- What’s good for the heart is good for dementia: low apoB, low inflammation, low oxidative stress.

- What’s good for the liver is good for dementia ie. metabolic health

- Exercise is the most powerful preventative measure, because it helps maintain glucose homeostasis and improves health of our vasculature and promotes healthy mitochondria (see chapter 11).

- Strength training is important. Grip strength was strongly and inversely associated with incidence of dementia.

- Sleep

- Hearing aids, as they promote socializing, intellectual stimulation and feeling connected.

- Brushing and flossing one’s teeth.

- Dry Saunas: There is suggestion that four sessions per week, at least 20 min per session reduces risk of Alzheimer’s by about 65% and cardiovascular disease by 50%.

- Hormone replacement for women during transition to menopause seems promising.

Chapter 11: Exercise

Exercise has the greatest power to determine how you will live out the rest of your life. Even a fairly minimal amount of exercise can lengthen your life by several years. Going from zero weekly exercise to just ninety minutes per week can reduce your risk of dying from all causes by 14%. Regular exercisers live as much as a decade longer than sedentary people . The fittest people have the lowest mortality rates.

Poor fitness carries a greater relative risk of death than smoking.

Exercise really does act like a drug. It prompts the body to produce its own druglike chemicals that help strengthen our immune system and stimulate the growth of new muscles and stronger bones, it helps with memory, helps with keeping the brain vasulature healthy and may also preserve brain volume.

VO2

Cardiovascular fitness, measured by maximum oxygen a person can use during intense exercise (VO2) is the most powerful marker of longevity. The more aerobic fit you are, the more energy you will have for whatever you enjoy doing.

When you jog around the block, your breathing quickens and your heart rate accelerates to help you extract extract and utilise more oxygen from the air you breathe, in order to keep the muscles working. And if you run up a hill, you will need even more oxygen. The fitter you are, the more oxygen you can consume to make ATP (the chemical fuel that powers our cells), and the faster you can run up that hill. Eventually, you will reach a point where you just cannot extract more oxygen from the air. The amount of oxygen you are using at that point is your VO2 max.

VO2 max is usually expressed in terms of volume of oxygen a person can use, per kilogram of body weight, per minute. An average 40yr old man will have a VO2 max of about 40ml/kg/min and an athlete will have a VO2 max in the high 60s. An unfit person in their thirties of forties might score only in the high 20ml.

The good news is that VO2 max can be increased via training (see chapter 12)

Muscle Mass and Strength

We lose muscle mass and strength with age, although those who exercise, lose less than those who don’t. Having more muscle mass and stronger muscles helps support and protect the body, and also helps maintain metabolic health because those muscles consume energy efficiently. Continued muscle loss puts our lives at risk. Someone with more muscle mass is less likely to fall and injure themselves.

It is important to maintain muscle mass at all costs. That’s why weight training is important.

The Centenarian Decathlon

The “centanarian decathlon” is a list of the ten most important tasks you want to be doing for the rest of your life. It helps us visualise exactly what kind of fitness we need to build and maintain as we get older.

Examples of the tasks on the list may include:

- Hike 1.5 miles on a hilly trail

- Get off the floor using one arm for support

- Pick a young child off the floor

- Carry two five-pound bags of groceries five blocks

- Lift a twenty-pound suitcase into overhead compartment of plane

- Have sex

- Climb four flights of stairs in three minutes

- Open a jar

Over the next thirty of forty years your muscle strength will decline by about 8-17 percent per decade – accelerating as time goes on. So a 40yr old man who wants to lift a thirty pound child when he’s eighty, must be able to lift about fifty to fifty five pounds now, without hurting himself. We need to be doing much more now to armour ourselves against the natural decline in strength.

Chapter 12: The Gospel of Stability

The three dimensions for which we want to optimize fitness are:

- Cardio: long steady endurance work (zone 2) and maximal aerobic efforts (VO2 max)

- Strength: build strength and muscle mass, while avoiding injury

- Stability: avoid injury while building strength, by having a solid foundation

Cardio: Zone 2

Zone 2 exercise means going at a pace slow enough that one can have a conversation, but fast enough that the conversation might be a little strained. It builds endurance for anything else we might want to do in life, and helps with cognition. Find something you enjoy doing, and do it for about 3 hours per week (4 x 45 minutes)

Zone 2 and Mitochondria

Aerobic exercise, done in a very specific way, helps us use glucose and fat as fuel but fatty acids can be converted to energy only in mitochondria. The healthier your mitochondria, the better you burn the fat and keep your fat accumulation in check, so we need healthy mitochondria to prevent chronic disease and metabolic dysfunction. Mitochondria decline in number and quality as we grow older, but they can regenerate with aerobic exercise, which is another reason why Zone 2 training is so important.

The ability to use both fat and glucose as an energy source is known as “metabolic flexibility”. Ironically, people with metabolic syndrome have little ability to tap into their fat stores – they burn glucose but not fat. So the people who need to burn fat are unable to unlock any of the fat to use as energy but well trained athletes are able to do so easily. (Zone 2 exercise can burn fat or glucose, but higher intensity requires glucose.)

(While we exercise, our glucose uptake increases as much as 100 times. Zone 2 exercise enables body to bypass insulin resistance in muscles to draw down blood glucose levels. )

VO2 Max

(see chapter 11 for VO2 explanation)

Your VO2 will decline 15%/yr after the age of fifty. To arrive at age ninety with sufficient fitness level, you should aim for VO2 levels of the top 2% of people two decades younger.

You can always improve VO2 max with training, no matter how old you are. Studies show that boosting elderly subjects’ VO2 max by 6ml (25%) was equivalent to subtracting 12 years from their age. What this means: if you are a 60yr man with VO2 max of 30, you are average. Boost to 35, you are now in top 25%, and you have aerobic fitness of a 50yr old. Boost it to 38, and you will have aerobic fitness of a thirty-something (!).

It is possible to increase VO2 max by 13% over 8-10 weeks of training, and 17% after 24-52 weeks but do not think of this as an 8 week project…it’s more like a 2 year project and you should train for as high VO2 max as possible.

Once your VO2 max falls below 18ml/kg/min it begins to threaten your ability to live on your own.

How to improve your Vo2 max: During your exercise, go 4 min at max pace you can sustain for that time, then 4 min of an easier pace at Zone 2 level (or as long as it takes to get to fully recovered). Repeat 4-6 times, then cool down. Do this at least once a week. For people new to exercise, introduce VO2 max training only after about 5-6 months of steady zone 2 work.

Strength

Muscle mass begins to decline in our thirties, and we lose muscle strength about 2 to 3 times as quickly as we lose muscle mass. And we lose power (strength x speed) two to three times faster than we lose strength. We therefore need heavy resistance training.

It takes much less time to lose muscle mass and strength than to gain it. It is very difficult to put on muscle mass in later life, especially once we are frail.

Bone Mineral Density (BMD) is just as important as muscle mass. It protects us from injury and frailty: Mortality from hip or femur fracture post 65 years is 15-35% in one year (ie. up to one third of those people are dead within the year). Bone density diminishes from our twenties, especially in women going through menopause who are not on HRT. The fix: optimize nutrition (focus on protein), heavy load bearing activity, HRT if indicated, drugs if indicated.

Strength training should include focus on:

- Grip Strength, which is a strong predictor of longevity. Walk for a minute with a weight in each hand. (The total weight carried should be 100% of body weight (men) and 75% for women). Alternatively, dead hang from a pull-up bar (two minutes for men in forties, and 90 seconds for women)

- Attention to both concentric and eccentric loading for all movements (must be able to lift weight up, and put it down, slowly). Must be able to step onto an 18 inch block, and step off (forward), taking 3 seconds for each move.

- Pulling motions, from all angles

- Hip-hinging movements, like squats

Chapter 13: The Gospel of Stability

(Note: This chapter includes lots of descriptions of exercises. I have not included these here, as I think it’s better to at least see them demonstrated on video, or work with a trainer. The author seems to agree, and has posted some of his own videos on peterattiamd.com/videos. You can also search Youtube for exercises that resonate with your needs. )

First, do thyself no harm. In order to go faster, you need to go slower. Do not do strength training until you have mastered stability. It is worth the extra time to build a solid foundation.

Stability lets us create the most force in the safest manner possible. The goal is to be strong, fluid, flexible and agile. Author does one hour of stability training twice a week, and 15 minutes on all other days.

DNS: Dynamic neuromuscular stabilization

DNS is based on our movements when we were babies. As children grow, their brain learns how to control the body and move correctly. As we grow up, and sit the whole day in chairs etc, we forget how to move our bodies. The point of DNS is to retrain our bodies – and our brains – in those pattern of perfect movement we learned as little kids. Every person needs their own training plan, and you can visit rehabps.com and posturalrestoriation.com to get started on further research.

Stability training begins with breath. Someone who is breathing hard and poorly while shoveling snow is putting themselves at increased risk of back injury. Proper breathing affects so many physical parameters: rib position, neck extension, the shape of the spine, even the position of our feet on the ground.

Our feet are literally the foundation for any movement we might make. Our toes are crucial to walking, running, lifting and decelerating or lowering. The big toe is especially necessary for the push off in every stride. If toe strength is compromised, everything up the chain is more vulnerable – ankle, knee, hip and spine. Toe yoga improves the dexterity and strength of our toes, as well as our ability to control them with our mind.

Feet are also crucial to balance. One test of this: stand with one foot in front of the other, and try to balance. Close your eyes, and see how long you can hold the position. Ten seconds is a respectable time. The ability to balance on one leg at the age of fifty and older has been correlated to future longevity, just like grip strength.

In addition to breath and feet, stability training should include focus on spine (the structure we most want to protect), shoulders, hands.

Chapter 14:

Can nutritional interventions extend and improve lifespan and healthspan, almost magically, the way exercise does? Author is not convinced. Thanks to the poor quality of “diet” science, we don’t actually know that much about how what we eat affects our health. There are forty thousand diet books on Amazon, and they can’t all be right.

There is no one diet that works best for every single person. Food molecules – which are nothing more than different arrangements of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and hydrogen atoms – also interact with our genes, our metabolism, our microbe, and our physiologic state. Each of us will react to these food molecules in different ways.

Our knowledge of nutrition comes from two types of studies: epidemiology and clinical trials.

Epidemiology

Researchers gather data on the habits of large groups of people, looking for meaningful associations or correlations with outcomes like cancer. This generates much of the “news” that pops up in our feed, like whether coffee is good for you, or bacon is bad for you . But it is incapable of distinguishing between correlation and causation. Add bad journalism, and we end up with confusion. The argument against epidemiology is that nutritional biochemistry is so complex, that epidemiology is simply not up to the task of disentangling the effect of any individual nutrient or food. “Epidemiology should go in the waste bin”.

Clinical Trials

They are more rigorous than epidemiology, and offer some ability to infer causality thanks to process of randomization, but they too are flawed. There’s trade-off between sample size, study duration and control. It is impossible to strictly control the nutritional intake of large groups of people, for a year – which is exactly what is often required.

Nutrition 3.0

The Nutrition 3.0 approach is scientifically rigorous, highly personalized, and driven by feedback and data rather than ideology and labels. It’s not about telling you what to eat, it’s about figuring what works for your body and your goals – and just as important, what you can stick to. The goal is to figure out not what diet works best “on average”, but what diet works best for you. That’s the next chapter.

Chapter 15: Putting Nutritional Biochemistry into Practice

Bad nutrition can hurt us more than good nutrition can help us. We need to focus on eliminating those types of food that raise blood glucose too much, but in a way that does not compromise protein intake and lean body mass.

SAD: Standard American Diet. Synonymous with added sugar, highly refined carbohydrates with low fiber content, processed oils, and other very densely caloric food. For the first time in human history ample calories are available to many people, but evolution has not prepared us for this situation. SAD wages war on metabolic health, and given enough time most of us will lose the war.

We have three options:

- Caloric restriction (eating less, but without attention as to what is being eaten)

- Diet restriction (eating less of something specific element)

- Time restriction (eating at certain times, or multi day fasting)

Caloric Restriction (CR)

If we take more energy than we require, the excess ends up in our adipose tissue, and can spill over to our liver and our muscles.

If you are eating SAD, you should probably eat less of it but If your diet is of high quality, then severe CR may not even be necessary. At the end of the day, avoiding a crap diet may be all you need.

With severe CR, you will have weakened immunity and possible muscle loss, and constant hunger. Could do more harm than good. You also need to track everything, and it is very difficult to stick to it.

Diet Restriction (DR)

Most common type of restriction this one can be highly individualized: you can impose varying restrictions depending on your needs. You can still end up overnourished because cutting out one food group does not mean you can eat as much as you like of everything else.

Everyone’s metabolism is different. What works for some can backfire for others. The real art to DR is not picking which foods you are eliminating, rather it’s finding the best mix of micronutrients to meet your goals, in a way you can sustain. (see below)

Time Restriction (TR)

Although fasting triggers many of the physiological and cellular mechanisms that we want to see, author does not recommend it to all his patients.

- 16 hours without food is not long enough to trigger autophagy

- Can miss protein intake target, and loss of muscle

- Affects activity levels

Nevertheless, it can be used to control caloric intake without inducing hunger, TR is then more of a discipline than a diet.

Worth noting that fasting can work for some, if no other dietary intervention has worked and where muscle loss is lesser of two evils.

Micronutrients

Alcohol:

Empty calorie source that offers zero nutrition value. Ethanol is a potent carcinogen, and chronic drinking has strong association to Alzheimers (via lack of sleep). Drinking alcohol also loosens inhibition around other food consumption.

On the plus side, it can dissipate stress.

Author recommends fewer than 7 servings per week, and no more than 2 on any day.

Carbohydrates

Primary energy source. Excess glucose is stored in body (see chapter 6). Each person will respond differently to an influx of glucose.

You can use CGM (control glucose monitor) to monitor your body’s reaction to glucose. This is a device that is easily implanted in your upper arm (easy to do yourself at home), and it gives continuous, real-time information on blood glucose levels. The patient can see, moment by moment, how blood sugar levels are responding to whatever they eat. The data then shows historical averages and variances. (You can buy a CGM by googling online).

Ideally, your average glucose level should be below 100mg.dL with a standard deviation of less than 15mg/dL. This corresponds to HbA1c of 5.1 percent, which is quite low. But worth it! This takes experimentation and iteration.

Your carb tolerance is heavily influenced by other factors, especially your activity level and sleep. A horrible night of sleep cripples our ability to dispose of glucose the next day.

Timing is important (you can game the system!) Eating a potato before exercise has a different effect to eating it while inactive.

Worth noting that CGM measures one variable, thus cannot on it own help you find the ideal diet. Eating only bacon can give you a great CGM reading, but it is not optimal. (Just like a bathroom scale would suggest smoking is good for you because you lose weight).

So, you also need to track: weight, body composition, ratios of lean mass and fat mass, and how they change. Use biomarkers such as lipids, uric acid, insulin, and liver enzymes.

Protein

The first thing you need to know about protein is that the standard recommendations for daily consumption are a joke. The US recommends 0.8g/kg which may be how much we need to stay alive, but not thrive.

Author sets minimum 1.6g/kg as a target, but data suggests that for active people with normal kidney function 2.2g/kg (or one gram per pound) is a good place to start. (7 grams per ounce (30g) of meat).

That’s a lot of protein to eat. And it should be spread out throughout the day, over at least four servings. One of them should be a whey protein shake. One serving can also be a high protein snack.

Note that with plant protein, only about 60-70% is available to be used by you.

Fats

Fat is essential, but too much can be problematic. Fats get a bad rap because of caloric content and because they raise LDL cholesterol, and thus heart disease risk.

Fats are source of fuel and building blocks for our hormones and cell membranes. Eating right mix of fats helps maintain metabolic balance, and also the health of our brain.

There are three types of fat:

- SFA, saturated fatty acids (white palm and coconut oil)

- MUFA, mono-unsaturated fatty acids (olive oil, safflower oil)

- PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids (Omega 6 and Omega 3). Omega 3 is made up of Marine (EPA, DHA) and Non-marine (ALA)

No food belongs to just one group of fats: all foods that contain fats typically contain all three categories.

Author suggests mix of: MUFA, 50-55%, SFA 15-20%, PUFA to fill gap. Also aim for 8-12% of EPA and DHA (easily measured with a blood test).

That means eating more olive oil, avocados and nuts, cutting back on butter and lard and reducing the omega-6 rich corn oil, soybean and sunflower oils. Look for ways to increase high omega-3 marine PUFA (salmon and anchovies, or capsules).

The science of fats is far from perfect, and individual responses need to be monitored.

Chapter 16: The Awakening

We need to sleep about seven and half hours per night. Sleep plays a major role in brain health, our cognitive function and our cognitive health. Even a single night of bad sleep has been found to have deleterious effects on our physical and cognitive performance. Sleep disturbances often precede the diagnosis of dementia by several years. Conversely, good sleep is associated with lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

Poor sleep:

- wreaks havoc on our metabolism and insulin resistance.

- causes stress, and stress causes poor sleep.

- changes the way we behave around food (we eat more when sleep deprived)

- is strongly associated with cardiovascular disease and heart attacks.

If you are struggling with sleep:

- Give yourself permission to sleep (mindset)

- Environment conducive to sleep: no light, no devices, no blue toned LED lights, temperature (keep it cool)

- No alcohol

- No naps

- Exercise in Zone 2 for 30 minutes, not within 2-3 hours of bed time

- Mentally prepare yourself for sleeping (try to get rid of thoughts that cause stress etc)

- Rule out obstructive sleep apnea (speak to your doctor)

If you are still unable to sleep, stop fighting it. Get up and do something meaningless but enjoyable (never give your insomnia a purpose).

Chapter 17: Mental Health

Medicine 3.0 thesis is that if we address our emotional health and do so early on, we will have a better chance of avoiding clinical mental health issues such as depression and chronic anxiety – and our overall health will benefit as well.

The key is to be as proactive as possible, so that we can continue to thrive in all domains of healthspan, throughout the later decades of our lives.

(The author goes through various possible interventions, but I have chosen not to sum them up here as they require careful consideration, not a quick sound bite).